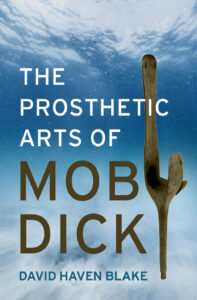

I have frequently written about American political culture and am the author of an award-winning book on presidential history. At the moment, however, The Prosthetic Arts of Moby-Dick feels like the most political of my books in its focus on democracy, wound collecting, and the role that Islamic cultures play  in American narratives of revenge. In the following commentary piece (first published on the Oxford University Press Blog and then republished by the Writers for Democratic Action Substack), I discuss the ways in which Melville anticipated our current political crisis. The piece begins:

in American narratives of revenge. In the following commentary piece (first published on the Oxford University Press Blog and then republished by the Writers for Democratic Action Substack), I discuss the ways in which Melville anticipated our current political crisis. The piece begins:

Like the white whale itself, Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851) seems ubiquitous across time. For nearly a century, readers have turned to Captain Ahab’s search for the whale that took his leg to understand American crises. During the Cold War, commentators debated Ahab’s Stalin-like powers. After the September 11 terrorist attacks, the question of vengeance took center stage. Was Ahab Mohammad Attah crashing an American Airlines jet into the World Trade Center’s North Tower, or was he George W. Bush searching for weapons of mass destruction in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq?

Donald Trump’s return to the presidency offers a different question about Melville, domination, and US political life: How do Americans gain power by claiming that they have been wronged? Trump continues to shatter political norms, but complaining about mistreatment is part of the nation’s DNA. As erratic and self-indulgent as it may be, Trump’s sense of injury stretches back to the series of grievances that the Declaration of Independence itemized about King George III. Continued at OUP Blog

purchase this hardcover volume, though if you would like Oxford University Press to publish a paperback, please visit the

purchase this hardcover volume, though if you would like Oxford University Press to publish a paperback, please visit the  The cover of a Norton Critical Edition often tells us where scholarship is heading. Midway through the writing of The Prosthetic Arts of Moby-Dick, I was pleased to see that Norton had put Ahab’s whalebone leg on its cover. The illustration, done by the Russian artist Oleg Dobrovolski, highlights the role that disability and prosthetics play in this novel. (Ahab is not the only impaired character in the book, and Moby-Dick is just one of Melville’s writings that meditate on injury, prosthetics, and disability.) How have you imagined Ahab’s ivory leg?

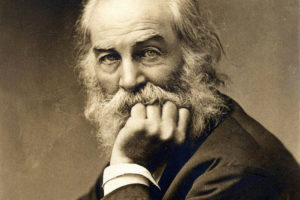

The cover of a Norton Critical Edition often tells us where scholarship is heading. Midway through the writing of The Prosthetic Arts of Moby-Dick, I was pleased to see that Norton had put Ahab’s whalebone leg on its cover. The illustration, done by the Russian artist Oleg Dobrovolski, highlights the role that disability and prosthetics play in this novel. (Ahab is not the only impaired character in the book, and Moby-Dick is just one of Melville’s writings that meditate on injury, prosthetics, and disability.) How have you imagined Ahab’s ivory leg? 2019 marks the 200th anniversary of Walt Whitman’s birth. Around the world, people have celebrated Leaves of Grass, gathering in

2019 marks the 200th anniversary of Walt Whitman’s birth. Around the world, people have celebrated Leaves of Grass, gathering in  Founded in 1815, NAR is the perfect magazine to publish this work. The oldest literary magazine in the United States, its past contributors range from Ralph Waldo Emerson and Frederick Douglass to William Carlos Williams and Flannery O’Conner. “The North American,” Whitman once told a friend, “is hospitable to new, strange views; invites, accepts, and that is a gift these days.” For my selection, I chose a single line from section 25 of “Song of Myself”: “My voice goes after what my eyes cannot reach” in which, I argue, the poet becomes a voyager, “his voice audaciously pursuing others like a lover, hunter, or follower of new gods.” You can read the short essay

Founded in 1815, NAR is the perfect magazine to publish this work. The oldest literary magazine in the United States, its past contributors range from Ralph Waldo Emerson and Frederick Douglass to William Carlos Williams and Flannery O’Conner. “The North American,” Whitman once told a friend, “is hospitable to new, strange views; invites, accepts, and that is a gift these days.” For my selection, I chose a single line from section 25 of “Song of Myself”: “My voice goes after what my eyes cannot reach” in which, I argue, the poet becomes a voyager, “his voice audaciously pursuing others like a lover, hunter, or follower of new gods.” You can read the short essay  The grant helped my students and me explore what fame meant before these powerful historical forces emerged in the 18th century and how it shaped such works as The Iliad, The Aeneid, the Gospel of Mark, and the Confessions of St. Augustine. In October, the NEH magazine, Humanities, published my reflections on teaching this course in an essay the editors titled

The grant helped my students and me explore what fame meant before these powerful historical forces emerged in the 18th century and how it shaped such works as The Iliad, The Aeneid, the Gospel of Mark, and the Confessions of St. Augustine. In October, the NEH magazine, Humanities, published my reflections on teaching this course in an essay the editors titled

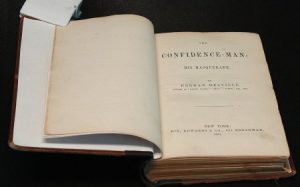

(for example, exactly how many con men are on board?), but each of the tricks depends on an expression of confidence in the world. When passengers question the con man or refuse to buy into his schemes, he urges them to open their hearts and speak with sincerity. “Ah, now,” he says in the guise of the buoyant Frank Goodman, “irony is so unjust: never could abide irony: something Satanic about irony. God defend me from Irony, and Satire, his bosom friend.” To state the obvious, Melville is winking at his reader. From its first paragraphs to its apocalyptic end, the novel provides a textbook example of irony: it says one thing and means another

(for example, exactly how many con men are on board?), but each of the tricks depends on an expression of confidence in the world. When passengers question the con man or refuse to buy into his schemes, he urges them to open their hearts and speak with sincerity. “Ah, now,” he says in the guise of the buoyant Frank Goodman, “irony is so unjust: never could abide irony: something Satanic about irony. God defend me from Irony, and Satire, his bosom friend.” To state the obvious, Melville is winking at his reader. From its first paragraphs to its apocalyptic end, the novel provides a textbook example of irony: it says one thing and means another What makes the Confidence Man so successful is that he swindles his victims not only of their money, but of the skepticism and critical thinking they need to successfully navigate their lives.

What makes the Confidence Man so successful is that he swindles his victims not only of their money, but of the skepticism and critical thinking they need to successfully navigate their lives.